Having significant PsuedoBulbar Affect (PBA) for many years after sustaining multiple traumatic brain injuries (TBIs), my PBA went undiagnosed until my post-intensive cognitive outpatient therapy at Mount Sinai (a TBI Model System) when I began volunteering on the inpatient TBI/Stroke floors. It was not until I met other patients with a similar condition (i.e., PBA) that I recognized what I had been experiencing had a diagnosable name other than the one I used when referring to these episodes of emotional dysregulation. Personally, I described them as “emotional seizures.”

As my exaggerated emotional episodes seemed to be related to what I called “Emotional Dysregulation” that’s where I began. During my research I stumbled upon an online Emotional Regulation study for people post TBI at Mount Sinai’s Brain Injury Research Center. Taking part in this study helped my Emotional Regulation but my “Emotional Seizures” remained.

I wanted to learn as much as possible about what was happening to me, about brain injury, and use that knowledge to empower myself, especially when faced with triggers and challenges. As someone with an interest in psychology, I recognized the importance of discovery and research. I did not have all of the answers and wouldn’t, but I wasn’t powerless.

I couldn’t speak when the emotional PBA was so intense and overwhelming –without question, that was one of the most difficult elements to deal with. If I was physically reacting to an emotion, then this feeling must be true, right? Sometimes I coped with the dysregulation and ‘emotional seizures’ through isolation or trying to limit exposure to/and avoiding serious emotional triggers. That included avoiding trying to speak under pressure.

Usually triggered immediately when experiencing a sad or traumatic thought, the response felt like it had a life of its own, and the intense reaction did not align with the situation. They hit when alone, around others, and while running. It was embarrassing and humiliating to me when others witnessed them. Having post TBI ultra-rapid cycling emotions helped trigger these episodes, so I could be crying one moment and laughing the next. These episodes made me feel even more disabled than the cognitive issues I was also dealing with (i.e., if I was physically reacting to an emotion, ‘Oh, then this feeling must be true right?’). It was as if my personality changed overnight, and I could not find a steady emotional state to adjust to. Neurologists thought my episodes were a type of seizure and had two inpatient hospital video-EEG trying to find an answer (I did not have an episode during EEG monitoring), and it was by default they thought the episodes were ‘Pseudoseizures’ and thus, completely in my mind.

I experienced extreme headaches, dizziness, passing out, hearing, vision, and vestibular difficulties, and my short-term memory was measured at 1-2%. I’ve flooded my house six or seven times because I just walk away, forgetting the water was even on. I wore earplugs, noise cancelling headphones, dark sunglasses in the subway just to get to rehab. Like, just trying to make it there in one piece and having PBA on the way, was total sensory overload. By the time I got there, I was cognitively and emotionally diminished. PBA took out the ability to think when it hit again and again, with extreme cognitive fatigue following.

A typical PBA episode for me lasted 20 seconds on average and up to one and a half minutes when they hit consecutively for the bad ones. It was intense… but I’m not one to give up.

PBA pronounced itself after my eigth concussion, a moderate one. In total, I have experienced approximately 18 different losses in consciousness. I call it the cumulative effect, particularly because each time you have a head injury your chances of having another one multiplies significantly.

Three years later, while I was running to my therapist’s office, my foot slipped into a hole on the sidewalk and immediately launched me across the pavement. My head bounced twice on the concrete, and I broke my collar bone. When I opened my eyes, I immediately knew something was wrong. It would take another three to four years of recovery. Brain injury symptoms and sensitivities started all over again.

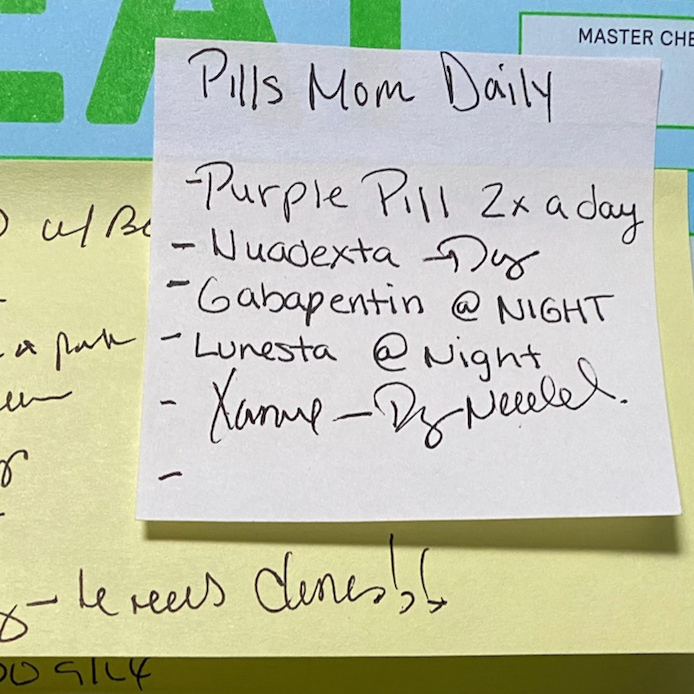

Honestly, it is a very difficult condition to live with. When one’s emotions are incongruent to the situation or exaggerated, a person has a tendency to believe they are actually feeling that way, versus just a neurological and emotional glitch. I had to self-advocate before I could finally try the Nuedexta. There was not a definitive answer as to whether I had PBA because medical professionals lack the information about the condition.

I’m not one to give up. When I saw another patient with symptoms very similar to mine, I read about PBA, and I discovered there was a medication that could be used to treat/lessen the intensity and frequency of the symptoms. “Let me just try it,” I told my psychopharmacologist, who was uncertain if the medication would be right for me but agreed to prescribe the medication as anything to help was on the table. By the third week of taking the medication there was a substantial drop in PBA episodes; this was absolutely life-changing in a positive way. Now several years later, I am still taking Nuedexta and happily PBA episode free!

I became a paid trainee at Mount Sinai, and later acquired the CBIS accreditation (requiring 750 hours of experience working with individuals with brain injuries). I also volunteered as interim President of the NYC chapter of the Brain Injury Association because they were going to shut the group down due to lack of leadership interest.

I have even been a court appointed guardian representing a friend/patient with Aphasia and PBA in an eviction case. This friend came to me for help because of my legal knowledge, as well as her condition (I was a trainee and Co-facilitator in a support group she was part of: we actually won the National Stroke award for Best Support Group). She was unlawfully evicted from her apartment by NYC police (and later per a court ruling) due to her aphasia and co-occurring PBA. I understood that she couldn’t speak when she was under stress. Because my PBA was treated, along with related aphasia, I was able to represent her and be her voice in court. The original eviction court ruling was overturned, and we won the case, thereby avoiding a travesty of justice and a homeless situation.

After moving to upstate New York, I helped coordinate support for caregivers and persons with brain injuries during the COVID-19 pandemic. I facilitated zoom meetings for respite, connection, and overall health and emotional well-being.

What I would tell someone else who had PBA or was experiencing symptoms is…

Advocate for yourself or find someone who can because you deserve it.

Find strategies that work for you because each brain injury can affect you differently. Running was a healing element for me. For others, it is a more creative outlet like painting. Whatever yours it – take the time to find it.

And to remember that even if you struggle with emotional regulation, sensory overload, or other significant brain injury secondary effects like aphasia, it doesn’t mean that your voice is any less valuable. Don’t give up. Time is your friend, and this too will change.

This story was co-authored by Sara Evelyne